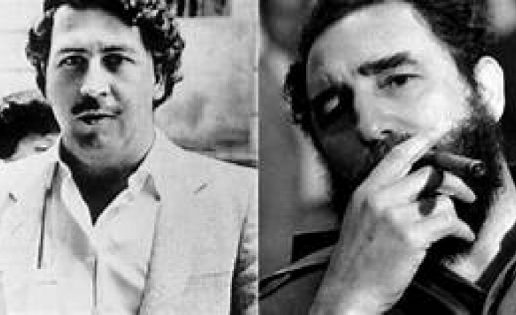

Introduction: Narco States and Pablo Escobar’s & Fidel Castro’s combined legacy

Until very recently, the relationship between the cocaine trafficking business model, terrorist groups, and politics was a phenomenon that would normally occur either in Latin America or as part of some Netflix series scripts – anyway, always far from the coasts and the borders of Europe.

Today, the convergence between these three occupations is a clear and present danger to the nations of Europe.

At the beginning of the 1980s, the term Narco State was used for the first time in Colombia to coin polities in which drug traffickers had earned substantial influence upon the political institutions of a nation.

In those years, 1982 and 1983, specifically, the Cártel de Medellín’s drug lord, Pablo Escobar Gaviria, succeeded in earning a seat in the Republic of Colombia’s Congress through democratic elections.

Since then, particularly across Latin America, the term Narco State has been widely used to define political systems in which the rule of law is entirely replaced by the power of transnational organized crime (TOC) groups.

There are two outstanding features that define any Narco State – power is in the hands of criminals and States structures end up adapting themselves to the wishes of TOC.

Firstly, within Narco States, the power of a country lies in the hands of TOC and its allies.

To create a Narco State, criminal groups tend to penetrate, co-opt, and weaken government structures to fully corrupt institutions, agencies and individuals of any given government’s defence, security, justice, and executive functions.

The experience of the last decades in Latin America taught us that once the checks and balances that protect the rule of law are sufficiently softened and corrupted to fall under the control of the TOC, Narco-States end up paving the way for the penetration of terrorist organisations into the countries they take control of.

That has been the case in Venezuela with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia o FARC) guerrillas, with the Spanish terrorist group Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA), and most recently with Hezbollah -the Party of Allah or the Party of God-, the Shiite Islamic terrorist group, which is financed and armed by the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Secondly, it is customary practice that standard States themselves allow this transformation of power to happen from which Narco States emerge.

In fact, oftentimes it is traditional States structures that become integral part of the criminal enterprise that Narco States represent.

So much so that those weakened State institutions create opportunities for security organizations, law enforcement officials, members of military institutions, or politicians to be co-opted by TOC.

Hence, criminal groups end up working and collaborating with police forces, judges, and the military in this process of penetration and transformation of States from within.

In short, Narco States do not leave ungoverned spaces within the countries they control – what changes in them is who exercises authority and power and whose interests they represent.

The expansion of TOC to control territories, to establish power constituencies of its own, and to set up front businesses, including private security companies, is limitless until it earns full capacity to run all functions that are usually associated with regularly functioning States.

During the 20th century, the three most notorious precedents of a Narco State building process attempt in Latin America happened in Bolivia, in Colombia, and in Peru.

In Bolivia, in 1980 and 1981, Colonel Luis García Meza’s Government had an Interior Minister, Luis Arce Gómez, who was directly involved in the drug trafficking business for which he had to leave the country – Arce took refuge in Taiwan.

Ernesto Samper, who served as Colombian president, between 1994 and 1998, developed his entire political career always under the suspicion of having been financed by drug money.

Lastly, in Peru, Vladimiro Lenin Ilich Montesinos, the immensely powerful head of the country’s National Intelligence during the 1990s, under Alberto Fujimori’s presidency, was connected to the drug trafficking business.

At the end, a so-called “Operation Siberia” precipitated Montesinos’ fall from power since it was found out that through such a scheme, he had bought Russian weapons from an Arab country with money provided to him by Colombian FARC.

Today, this convergence between drug trafficking and politics is a highly adaptive structure, which blends the best of Pablo Escobar’s business model organization, of Fidel Castro’s communist ideology, and of international terrorism networks.

This web of interests was adapted to the expectations of the new century – this is what their followers cunningly and euphemistically call 21st century’s Socialism.

Within Narco States’ division of labour across Latin America, Cuba is the Western Hemisphere’s communist Rome.

The former presidents of Bolivia, Ecuador, and Brazil, Evo Morales, Rafael Correa, and Lula da Silva, respectively, are fervent believers of that form of communism at a time in which ideology replaced religion in Latin America, and they all get their marching orders from Cuba.

In the case of the late former president of Venezuela, Hugo Chávez, in addition to ideology, he did grow a sincere feeling of affection for Fidel Castro, even though Castro despised him.

Ironically, however, the great ideologue of this political-criminal project was Pablo Escobar Gaviria, not Fidel Castro.

Indeed, it was Escobar who blueprinted and implemented this special relationship between his business model and FARC or ETA terrorists.

In fact, nowadays, one of the most critical relationships for Narco States’ business model is Jihadist Islamic terrorism since its transnational tentacles immensely facilitate the logistics, the shipping, and the distribution of cargoes, particularly across the African continent on their way into Europe, and the profit laundering, the front businesses setting up, and all sorts of spun-off lines of business development from gold melting to arms or human trafficking in all parts of the world.

And at the top of the vertices, Venezuela’s Military Institution sits as the ultimate guarantor of its Narco State operating system functioning, while this whole criminal organization relies on Cuba’s polity as its mastermind.

This criminal and political structure is a seamlessly globalised one and has big and complementary international ambitions, which are projected both towards the United States (US) and towards Europe.

On the one hand, it is aimed at a gray zone type of confrontation against the US, the “Empire“, the always despised American enemy, in what clearly is an asymmetric and irregular war of sorts through hybrid methods.

On the other hand, it seeks to meet the objective of reinforcing beachheads of its own in Southwestern Europe as a gateway into the Old Continent.

Venezuela currently is Latin America’s Narco State par excellence.

The Armed Forces of Venezuela are the central nucleus of the so-called Cártel de los Soles (Cartel of the Suns) -name taken after the symbols on the Venezuelan generals’ uniforms epaulettes-, with which the country’s Customs Service collaborates subordinately and closely.

Venezuela’s President, Nicolás Maduro, President of the Venezuelan National Assembly, Diosdado Cabello, and Venezuelan twice minister of Industries and National Production and minister of Oil, Tareck El Aissami Maddeh (a.k.a. TEAM) are at the head of this Narco State.

The case of Nicolás Maduro is intriguing since he was a Cuban regime’s bidding after the death of his predecessor, Hugo Chávez, and the truth is that not much is known about him -not even his place of birth-, since he does not come from the established Venezuelan power groups, although it is documented that he had been educated in Cuba.

So far, choosing Maduro has been a success story for Cuba, although this strategic choice went through a delicate moment when, in 2019, in the heat of the anti-government demonstrations promoted by opposition leaders Juan Guaidó and Leopoldo López, Maduro expressed his willingness to leave the country for good.

That runaway attempt provoked the intervention of Raúl Castro – who, at the time, was still the first secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba – to reject and obstruct that potential desertion.

The reality is that Venezuela has become a country in which, in practice, there is an unstable balance between criminal gangs with an established division of territory and functions between FARC’s many splinter groups, the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, or ELN), and terrorist Islamic Hezbollah.

In the value chain of coca cultivation and production business model, Colombia is king.

According to the United Nations (UN), Colombia is the world’s leading coca producer, and its main market is the US, where the product is exported through Mexico.

Peru and Bolivia are the world’s second and third largest producers of coca, respectively, and their target markets are in Europe, where coca is exported through Brazil and, subsequently, through West African countries, both of which are stopovers in that logistic chain.

Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia enjoy the competitive advantage of benefiting from a sweet combination of both climate and highlands so conducive to coca cultivation.

Despite this, because of the investment made in Research, Development, and Innovation (RDI), the business model of drug trafficking is beginning to experiment with coca growth inside the Amazonia to the point that it is expected that Brazil could eventually become one of the world’s larger coca producers.

Argentina, for her part, ceased to merely be a transit country within the drug trafficking logistic chain and the “hell kitchens” are already professionally installed in that country.

Venezuela, on the other hand, is not a coca producer itself, but plays within the business model of drug trafficking a role equivalent to a commercial office and port of departure for everything that is produced by the Colombian cooks.

The great added value that Venezuela brings to this business model is political power support to guaranteeing transactions, which is such a necessary and critical resource for all those operations to be successfully completed.

However, it is worth underlining that since Nicolás Maduro became president of Venezuela in 2013, the country’s cocaine trade has undergone revolutionary changes.

Today, Venezuela is at risk of becoming the world’s fourth cocaine-producing country.

And the Maduro regime has positioned itself as the gatekeeper to the country’s drug trade, controlling access to cocaine’s riches not only for drug traffickers but also for corrupt politicians and the military-embedded trafficking network of the Cártel de los Soles.

This complex and sophisticated structure of communist and authoritarian regimes, drug trafficking, and international terrorism has limitless ambitions to expand this well-connected business model that brings drug money, arms, and politicians together.

At the present time, a perfect storm has been unleashed upon three of the four Pacific Alliance member States -Peru, Chile, and Colombia, while President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s (a.k.a. AMLO) Mexico is being left on the side-lines, at least for the time being- and Brazil.

The reason for this assault has to do with the fact that Peru, Chile, and Colombia, in addition to Mexico, created the Pacific Alliance in 2011 as an economic and development initiative against communism.

Since then, the Alliance had become the linchpin of a way of doing business on the continent, whose key to this formula lies in the articulation of forces beyond territorial borders as a mechanism of political and economic cooperation and integration that seeks to find a space to promote greater growth and greater competitiveness for their respective economies.

The Pacific Alliance member States were confident that this would be possible through a sustained advancement of a free movement of goods, services, capital, and people across their respective geographies.

In short, the Pacific Alliance was born to protect free trade, private property, and democracy throughout the continent and, by extension, to confront the coalition of countries sympathetic to Chavista Venezuela and communist Cuba.

Now Peru, Chile, Colombia, and Brazil are in the first line of assault by a criminal phenomenon that wants to take, to exercise, and to extend its political power without limits and for its partners’ benefit’s sake only.

The rule of law is seriously threatened in Latin America and is also under clear and present danger in Europe, in general, and in Southwestern Europe, in particular.

This is so because Narco States -current and future ones- need to occupy all the domestic and international power space available and overthrow or undo the systems which are built upon the separation of powers, the rule of law, and the respect for individual freedoms*.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

* ECR Eurolat Summit: “EU and Latin American main enemy: the narco regimes”, www.ecrgroup.eu, June 17, 2021; and “Venezuela’s Cocaine Revolution”, InSight Crime, May 2, 2022.

NB: All information and data about the facts and people in this article were taken from open and public sources, which are cited here. Any errors they may have made are not attributable to the author of this article, but to those of the publications from which they were taken. This series of articles was completed on July 29, 2022.

EconomíaEspañaMundoOtros temasUnión EuropeaYihadismo

Tags

- "Hell kitchens"

- "Operation Siberia"

- 1980

- 1980s

- 1981

- 1982

- 1983

- 1990s

- 1994

- 1998

- 2011

- 2013

- 2019

- 2021

- 2022

- 20th century

- 21st century's Socialism

- ABC

- Access

- Added value

- Advance

- Advantage

- Affection

- African continent

- Agencies

- Alberto Fujimori

- Allah

- Alliance

- Allies

- Amazonía

- Ambitions

- América

- American enemy

- AMLO

- and Innovation

- and Innovation (RDI)

- Andrés Manuel López Obrador

- Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO)

- Anti-government demostrations

- Arab

- Arab country

- Argentina

- Armed Forces

- Armed Forces of Venezuela

- Arms

- Arms trafficking

- Article

- Articulation

- Assault

- Assembly

- Asymmetric war

- Attempt

- Author

- Authoritarian regimes

- Authority

- Balance

- Beach

- Beachheads

- Believers

- Benefit

- Birth

- Bolivia

- Borders

- Brazil

- Business

- Business development

- Business model

- Business model organization

- Businesses

- Cabello

- Cachinero

- Capacity

- Capital

- capital and people

- Career

- Cargoes

- Cártel

- Cártel de los Soles

- Cártel de Medellín

- Cartel of the Suns

- Castro

- Century

- Chain

- Changes

- Chávez

- Chavista Venezuela

- Check

- Check-and-balance

- Check-and-balance system

- Chile

- Choice

- Clear and present danger

- Climate

- Coalition

- Coasts

- Coca cultivation

- Coca cultivation and production business model

- Coca producer

- Coca production

- Cocaine

- Cocaine trade

- Cocaine trafficking

- Cocaine trafficking business model

- Cocaine's riches

- Colombia

- Colombian cooks

- Colombian FARC

- Colombian president

- Colonel

- Colonel García Meza

- Colonel Luis García Meza

- Combination

- Commercial office

- Communism

- Communist Cuba

- Communist ideology

- Communist Party

- Communist Party of Cuba

- Communist regimes

- Communist Rome

- Companies

- Competitive advantage

- Competitiveness

- Confident

- Confrontation

- Congress

- Constituencies

- Continent

- Convergence

- Cooks

- Cooperation

- Correa

- Corrupt politicians

- Country

- Criminal enterprise

- Criminal gangs

- Criminal groups

- Criminal organization

- Criminal phenomenon

- Criminal structure

- Critical resource

- Cuba

- Cuba's polity

- Cuban regime

- Cuban regime's bidding

- Cultivation

- Custom

- Custom Service

- Danger

- Data

- Defence

- Defence function

- Democracy

- Democratic elections

- Demonstrations

- Departure

- Desertion

- Development

- Development initiative

- Diosdado Cabello

- Distribution

- División

- Division of functions

- Division of labour

- Division of the territory

- Drug

- Drug lord

- Drug money

- Drug trade

- Drug traffickers

- Drug trafficking business

- Economic and Development initiative

- Economic Cooperation

- Economic initiative

- Economic integration

- Economies

- ECR

- Ecuador

- El blog de Jorge Cachinero

- Elections

- ELN

- Empire

- Enemy

- Enterprise

- Epaulettes

- Ernesto Samper

- Errors

- Escobar

- Established power groups

- ETA

- ETA terrorists

- Europe

- Euskadi Ta Askatasuna

- Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA)

- Evo

- Evo Morales

- Executive

- Executive function

- Expansión

- Expectations

- Experience

- Facts

- FARC

- FARC terrorists

- Fidel

- Fidel Castro

- First secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba

- Followers

- Forces

- Fórmula

- Free movement of goods

- Free trade

- Freedoms

- Front businesses

- Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia

- Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC)

- Fujimori

- Functioning States

- Functions

- Gatekeeper

- Gateway

- Geographies

- God

- Gold

- Gold melting

- Goods

- Government

- Government structures

- Gray zone

- Groups

- Growth

- Guaidó

- Guarantor

- Guerrillas

- Head

- Heads

- Heat

- Hell

- Hezbollah

- Highlands

- Hugo Chávez

- Human trafficking

- Hybrid methods

- Ideologue

- Ideology

- Individual freedoms

- Individuals

- Industries

- Influence

- Information

- Initiative

- Innovation

- InSight Crime

- Institutions

- Integration

- Intelligence

- Interests

- Interior Minister

- International ambitions

- International terrorism networks

- Intervention

- Investment

- Irregular war

- Islamic Republic of Iran

- Jihadist Islamic terrorism

- Jorge Cachinero

- Juan Guaidó

- Judges

- Justice

- Justice function

- King

- Kitchens

- Labour

- Latin America

- Law

- Law enforcement

- Law enforcement officials

- Leaders

- Legacy

- Leopoldo López

- Linchpin

- Lines of business development

- Logistic chain

- logistics

- Lord

- Luis Arce Gómez

- Luis García Meza

- Lula

- Lula da Silva

- Maduro

- Marching orders

- Market

- Mastermind

- Mechanism

- Medellín

- Member States

- Members

- Methods

- México

- Military

- Military Institution

- Military institutions

- Minister

- Minister of Industries and National Production

- Model

- Moment

- Money

- Montesinos

- Morales

- narco

- Narco-States

- Nation

- National Assembly

- National Intelligence

- National Liberation Army

- National Liberation Army (ELN)

- National Production

- Nations

- NB

- Necessary resource

- Netflix

- Networks

- Nicolás Maduro

- Objective

- Occupations

- Office

- Old Continent

- Open and public sources

- Open Sources

- Operating system

- Operation

- Operations

- Opportunities

- Opposition leaders

- Orders

- Organizations

- Organized Crime

- Pablo Escobar

- Pablo Escobar Gaviria

- Pacific Alliance

- Partners

- Party

- Party of Allah

- Party of God

- Penetration

- People

- Perfect storm

- Perú

- Phenomenon

- Place

- Place of birth

- Police

- Police forces

- Political and economic cooperation

- Political and economic integration

- Political career

- Political cooperation

- Political institutions

- Political integration

- Political power support

- Political structure

- Political systems

- Political-criminal project

- Politicians

- Politics

- Polities

- Port

- Port of departure

- Power

- Power constituencies

- Power groups

- Practice

- Predecessor

- Presidency

- President

- President Andrés Manuel López Obrador

- President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (a.k.a.

- President of Venezuela

- Presidents

- Private property

- Private security companies

- Process

- Producer

- Production

- Profit

- Profit laundering

- Project

- Property

- Public Sources

- Publications

- Rafael Correa

- Raúl Castro

- RDI

- Reality

- Refuge

- Regimes

- Relationship

- Religión

- Republic

- Republic of Colombia

- Republic of Colombia's Congress

- Research

- Resource

- Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia

- Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC)

- Revolutionary changes

- Role

- Rome

- Rule

- Rule of law

- Runaway

- Runaway attempt

- Russian weapons

- Samper

- Scripts

- Seat

- Secretary

- Security

- Security companies

- Security function

- Security organizations

- Separation of powers

- Series

- Series scripts

- services

- Shiite Islamic terrorist group

- Shipping

- Siberia

- Socialism

- Sources

- Southwestern

- Southwestern Europe

- Spaces

- Spanish

- Spanish terrorist separatist group

- Special relationship

- Splinter groups

- Standard States

- States

- States structures

- Stopovers

- Storm

- Story

- Strategic choice

- Success

- Success story

- Suspicion

- Symbols

- Systems

- Taiwan

- Tareck El Aissami Maddeh

- Tareck El Aissami Maddeh (TEAM)

- Target markets

- TEAM

- Tentacles

- Term

- Territorial borders

- Territories

- Territory

- Terror

- Terrorism networks

- Terrorist

- Terrorist groups

- Terrorist organizations

- Terrorists

- Time

- TOC

- trade

- Traffickers

- Trafficking

- Trafficking network

- Transactions

- Transformation

- Transformation of power

- Transit country

- Transnational Organised Crime (TOC)

- Transnational Organized Crime

- Transnational tentacles

- Truth

- UN

- Ungoverned spaces

- Uniforms

- United Nations

- United Nations (UN)

- United States

- United States (US)

- US

- Value

- Value chain

- Venezuelan established power groups

- Venezuelan generals

- Venezuelan generals' uniforms

- Venezuelan National Assembly

- Vertices

- Vladimiro Lenin Illich Montesinos

- Vladimiro Montesinos

- Weapons

- Web

- West African countries

- Western Hemisphere

- Willingness

- World