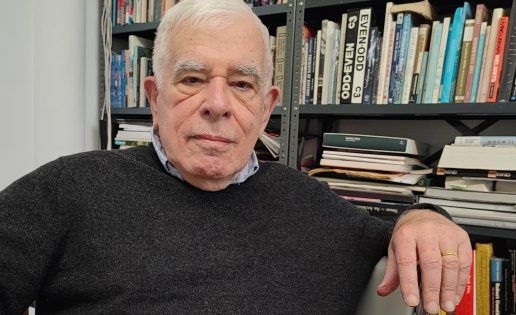

This interview was held at the beginning of February at Peter Eisenman’s office.

The last time I visited the place about fifteen years ago it was a hive buzzing with activity, but on that morning it was almost empty, somehow mirroring the hibernal lethargic atmosphere that seemed to have taken hold of Manhattan. Devoid of vim and vigour, Manhattan looked strange, a reflection of the general mood after having experienced a global epidemic. Nothing was hinting at the advent of that better world that was supposed to arise once the virus would be gone. It was the same old world, only more miserable and full of fear.

Meeting with Eisenman feels timely. Now probably is the right time to speak with experienced people like him, individuals who walked the path of the 20th century and left a meaningful trace there, in order to discover their thoughts and feelings about the good and the bad of the past and about their place in the present time – a time which appears just as haunting and unanticipated as the atmosphere in Manhattan in that early morning of that day of February 2022.

I think the last time I met with you for an interview was while the building of Ciudad de la Cultura was in progress. It was probably the most exuberant triumph of the so-called iconic architecture in Spain at the time. However, it never came to be realised as it had been initially envisaged.

People misunderstood what Manuel Fraga intended to do. The Ciudad de la Cultura was never meant to be a monument to him. He wanted to bring culture close to young people and he thought that this project would be a way to attract people to Santiago de Compostela. In other words, to have something that would be world-class, a cultural centre where every summer a festival would be held. It was a great idea. However, when he died, the people in his own party rejected the project.

In my opinion, Fraga was a fantastic human being. He was great to work for and we built something which was really extraordinary. The Ciudad de la Cultura project was really interesting and it would have been finished would have Fraga lived.

It seems the project was conceived by him under the influence of the Guggenheim Effect.

Santiago is an area where the reduction of the younger population is becoming problematic. So, Fraga had this idea to bring art, music, film…in a summer festival that would be held in these buildings. His idea was brilliant and he almost achieved it. He understood exactly what the project was about, even though it was a crazy one. He was seeking everything necessary for bringing Galicia back and had everything lined up to construct those six buildings.

Examining the project in hindsight, don’t you think the scale was disproportionately huge? Its surface is exactly as large as Santiago de Compostela’s old district.

It had to be too big. Manuel Fraga decided it. We did what he wanted. He voted for us to win this competition, which all the major architecture studios of the world had entered: Bofill, Koolhaas, Libeskind, Nouvel…

To me it is still a great idea and it is still remains, whatever it is. I’ve been there and I think it is really an intriguing thing. They had the budget to finish it at the time, but then the new guys arrived and took it away arguing that it was Fraga’s project.

I must mention also that Andrés Perea, the architect in charge of the project in Spain, was a great guy.

Would you stick to the same concept and design were it to be built today?

Yes, absolutely. I would build the same project. I am usually very critical of my work but in this case I think it would still be an exciting project. If you go there, it still is.

Maybe that has been a totally uchronic question. The call for this competition was made in 1999. The world was a rather different place at the time. In architecture, as I mentioned before, it was the era of iconic buildings.

But Jean Nouvel, Rem Koolhaas, Christian de Portzamparc, Frank Gehry, Wolf Prix… are still making iconic buildings today. Iconic projects are still there but that is not the spirit of our time.

Architecture is a cultural phenomenon, it has always been. It reflects culture and right now there is not much energy in contemporary culture toward physical buildings but toward media and social networks. All these things have moved the idea of the icon, of the object, to the Internet and social networks.

So, what does the future hold? And I am particularly referring to the culture of architecture. Before starting this interview, we have been talking about the passing of Oriol Bohigas and Federico Correa, figures who were part of a generation of intellectual architects, fully committed to the society and culture of the time they belonged to. What is your view about this present time?

Everything goes up and down. Culture is always this way. The 16th century was a wonderful time in Northern Italy, the 17th century it went down, then another glorious period came back in the 19th century…

Right now, they want women to be at the head of everything. That’s the culture today. Women almost didn’t exist when I was studying architecture. There were few female students of architecture and very few women doing architecture. And architects in the Western world do not refer these days to names like Bohigas or Correa or Moneo, they refer to Shanghai or Beijing. That is another important cultural shift, too.

True. Europe has stopped being culturally relevant.

However, for me it still is. I love Europe. I am still writing about Alberti, for example. I am doing a book on Alberti at the moment. I am having a major exhibition in Shanghai next year, I am doing a project in Tbilisi (Georgia). I am all over the world, but I am still a Westerner.

Another part of this cultural shift you have just mentioned is the elimination (and almost vilification) of the word “icon” as the central concept of the architectural vocabulary. It has been substituted by the terms “sustainability”, “environment”…

When you are talking about the environment, you are talking about something different to building in concrete. Architects don’t build in concrete because it is problematic, but we can’t go back to building in wood either, as we would be harming the environment by cutting down large numbers of trees. We can’t go backward, we must find a way to build within the environmental constraints. We have physical constraints and structural loadings.

I am not for these new buildings that have been built in New York. I don’t think they are architecture or icons. I think they are just a commercial thing. When you see all the traffic on the street and the people go to and back from work and they can’t find a taxi, the street is dirty… I think there is a height limit. You don’t have this kind of things in Madrid, the scale of Madrid is fabulous, like Barcelona’s. I don’t think you need super-tall buildings.

Yes, every time I come to New York I find a new recently-built skyscraper and I must agree with you: none of them is a patch on the Empire State Building. Not that they should be, of course, but I understand you mean they are pointless and vapid from an architectural point of view.

Yes, and the thing is that the culture needs iconic buildings in each age. The Modern period needed icons, just like the postmodern period did and the post-digital period in which we are right now does.

It is interesting you note we are in the post-digital period now. What happened to the Digital era?

I don’t think architecture is in a good period right now.

Italians have the word “progetto” which means to have an idea about work. Not many architects today have a progetto. Aldo Rossi and Mathias Ungers did, Rafael Moneo and Alvaro Siza do, but there aren’t many left. Those who did are already gone. Progetto means to have an idea about work, about what was important in history and is still important to day, it is not just about work.

Where are most of those digital architects today?

Were these digital architects as intellectually remarkable as they pretended or were assumed to be or was it a case of sheer luck: people who happened to be doing a specific kind of thing at the right place at the right moment?

I think that Gregg Lynn and Iñaki Ábalos for instance are still doing interesting things.

Society doesn’t appreciate architects in the same way it did. These guys are still around but the problem is, as I have said before, that the criteria for iconic has changed and the building needs to be environmentally and materially sound. It needs to be different things than those constituted iconic before. That is what I think has happened. Rafael Moneo is still there but the criteria that he is presented with make him difficult to produce the thing he would produce. The same applies to Arata Isozaki, Jean Nouvel…

The criteria of what constituted a culturally iconic building have changed and the people who are producing them have changed.

I would mark 2008 as the year when this shift started. Economies hit rock bottom then, a severe economic crisis broke out and household names such as Zaha Hadid, Jean Nouvel, Jacques Herzog, Norman Foster… were replaced by Alejandro Aravena, Francis Kéré and the likes, architects who embodied what we might call these new criteria of what constituted a culturally significant building.

Kéré is a very good architect. Aravena, on the other hand, doesn’t produce anything iconic. The new criteria for success is an empty icon. This applies to Lacaton & Vassal as well. That is the nature of the culture today: it doesn’t want iconic buildings the way they were. Lacaton & Vassal and Aravena are figures who belong to different generations, and they are what we might call anti-heroes.

Does culture need anti-heroes rather than heroes these days?

Yes, for sure.

Many architects feel clearly uncomfortable about the idea of producing (or having produced) icons.

What I think is that this is not the time.

What makes the idea of the zeitgeist? In the Modern era, there was a zeitgeist for these new white rationalist buildings. Rossi created La Tendenza in the 1970s, embodying the new rationalist thinking and as a reaction again individual expressionism that came after the war with figures like Eero Saarinen. Then came Post-modernism, making expressionist buildings. Afterwards came the digital.

Wouldn’t Deconstructivism stand between Postmodernism and digital architecture? Do you recognise yourself as a deconstructivist architect or would you argue that Deconstructivism was an invention by Philip Johnson?

I would say it was an invention of Philip Johnson, but I am teaching Deconstruction now.

I don’t believe in Deconstructivism, that was something devised by Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley. I am interested in the philosophical Deconstruction, in the approaches developed by Jacques Derrida and Bernard Tschumi.

I think that the Deconstructivism exhibition at MoMA in 1988 threw the Postmodern out of the window, which no longer had an edge like the Decon did.

Was Deconstructivism then Philip Johnson’s attempt to finish off Postmodernism somehow?

I don’t think he thought that was going to happen. It did happen but I don’t think he was necessarily for anything. Philip loved play.

Derridean Deconstruction talked about three things: Structure, which is not the kind of structure that happened in the late 19th century but a structure that was real. They also brought in the idea of sign, meaning the thing had to communicate but not on a graphic level, that is to say in an internal level. The third thing, and that was really important, was play. It didn’t have to be a one-on-one relationship between sign and structure, it could be changed. This is what Deconstruction was and it is not exactly what the show at MoMA displayed.

I was one of the few people who were interested in Deconstruction from this philosophical point of view but that is all gone. The digital changed the world and Greg Lynn is one of the people who transformed it. I would say Patrik Schumacher is responsible, too.

He is actually the person who led Zaha Hadid to adopt digital technology.

I think he is a very serious architect.

A building like Vitra’s Fire Station could be considered a good example of Deconstruction?

I wouldn’t say so.

What about the Jewish Museum in Berlin by Daniel Libeskind?

I would agree on that one.

Which one of your buildings would you mention as an example of Deconstruction?

I would either say the DAAP in Cincinnati and Ciudad de la Cultura in Santiago de Compostela.

In the latter you mix Deconstruction with digital technology.

Because of the people who were working with me. Greg Lynn was working with me.

Lynn always says I started the digital, but I was never interested in it. The digital is not about what Derrida calls “free play” and the whole idea of Deconstruction was the free play between the thing, the structure and the sign. There wasn’t a one-to-one relationship. The Albertian idea of part to whole which was essential to the digital appeared to me as retrogressive, not progressive.

I still believe this, and this is the reason why I am writing a book on Alberti, because he was the first one to say that the part to the whole is important.

Is there a real awareness of the importance of the history of architecture these days? My impression is that this importance is being dangerously downplayed, even ignored. Today, for many students, the beginning of the history of architecture dates back to Rem Koolhaas.

However, it is something essential to learn. How can you do anything if I tell you “make me a good building”? How can you understand what is good today? How do you know what good is? How do you know what is building today? You have to know history. You have to be able to say “in relation to the 19th century this is good or bad, in relation to the 16th century this is good or bad”.

People are saying today that Gaudí is the first postmodern architect. It is simply absurd. He didn’t have anything to do with that.

Yet, it is the kind of boutade or stupidity that can be created and easily swallowed when there is no solid knowledge and critical capacity. To me, the lack of interest in expanding their knowledge by looking back to history that college students have these days is absolutely shocking. Intellectual laziness is probably the main feature and largest problem of our time, it does not only affect the youngsters, but seeing them enquiring what is the point in reading, for instance, is seriously worrying, the most telling sign of how much worse this cultural decline will become.

I have said it: this is not a good time. Students don’t know history because they are not interested. Society doesn’t make them be interested. Media is what is interesting for them.

You are an architect but you are well-acquainted with philosophy and other disciplines, this is something that wasn’t so uncommon in your generation. However, I daresay today it would be extremely difficult to find an architect whose education could even match the one that architects from preceding generations had and continued to expand throughout their lives.

That is true, but I insist again: the world has changed.

To understand Deconstruction, Post-Structuralism, Roland Barthes, etcetera, you have to understand Lacan’s texts. Lacan’s texts encourage what they were doing.

The context has changed and Michel Foucault, Roland Barthes, Gilles Deleuze or Lévi-Strauss are out of touch with what the context is today. The context today wouldn’t support these kinds of people. The world has changed, you are the anachronist by being interested in these things.

But if we don’t mend our ways…

We cannot change the future. This is not our responsibility. Nobody said we should change anything. I am doing my work but it is different than it was twenty-five years ago. It is not the same because the context is different.

I must agree. Thinking of those images of the UIA Congress in 1996 in Barcelona, the kind of euphoria pictured in them no longer exists or could not be portrayed in the same way.

We wouldn’t have such an event these days. It doesn’t happen anymore. Nobody is having Moneo speaking in front of a crowd of thousands in a plaza in Barcelona.

But the reason for this might be the fact that people are not interested in culture anymore. You have rightly pointed out at the fact that people are more interested in media. Media uses cultural products but it doesn’t create or nurture culture.

The culture has changed. And culture is the context into which we make art. We do painting, sculpture, film, video… When I look at art magazines today I wonder “what is this?”, “what is the meaning of this?”. The meaning has to do with who is doing it, in other words you just cannot assume it is a white male. Everything has changed, for sure.

There is absolutely no future for humanism?

No, it is finished, like democracy. Do people want democracy these days? What is the meaning of “democracy”?

All the systems of the past, like democracy and capitalism, are under question and the culture of these things is under question. And I shouldn’t be doing anything because I am out of the framework of these guys. I believe in democracy, I believe in humanism, I believe in individuals. I teach that. For me Deconstruction is still part of the humanist ethos, you need Deconstruction to save humanism and that is what I do.

Democracy is over now, people don’t know what it means.

Has Populism played a role in this? The emotional side has taken over and relegated reasoning.

Yes, that is the reason. But we have to change.

Is there a real possibility for change?

(Laughter) You keep asking me this, and I have no answer. I am no guru.

You are a wise old man.

I am only old and this is not my time. It is not my time. And to think that I can change that is something I am not interested in. I am enjoying my life, I love my wife and my children, I love my work. I am here. Basta cosi.

(Portrait of Peter Eisenman: Fredy Massad)

(With thanks to Brian Gallagher and Erdem Tuzum.)

CríticaEntrevistasOtros temas